|

| Words by The Curmudgeon. Title image compliments of Green Ornstein. |

[WARNING: The following contains spoilers for Alan Moore's 1986 graphic novel, Watchmen. If you haven't read Watchmen, I SERIOUSLY RECOMMEND IT. If you have, or you don't mind the odd spoiler, read on!]

Special thanks to Green Ornstein for providing the title image!

I can’t help but feel a trifle trepidatious over the recent

absorption of Alan Moore’s Watchmen (1986) into the rest of the DC

Universe. Of course, Moore’s original text was always a property of DC comics,

seeing publication under their banner in 1986-87. But it was never a part

of the universe which DC had established. This could be taken as implicit,

given that none of the flagship franchise heroes of DC’s monopoly make so

much as a cameo in Moore’s world. Those familiar with Watchmen

will know that there are even major historical events which unfold in its timeline

– a major law, for example, which mandates the conscription of

superheroes into governmental control – which set it at a tangent from DC’s

ongoing mythos. Unfortunately, the fact of infinite earths and inter-dimensional travel – staples of DC’s expansive storytelling – make it so that the

aforementioned absorption of Moore’s foundational text is completely possible,

and absolutely canon.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

The discussion here, however, doesn’t concern the literal

possibility of blending Watchmen into the rest of the amorphous glob

that is DC’s conglomerate. It’s a matter of whether or not it makes sense

to do so. After all, in Moore’s own words, Watchmen seemed to take the

mainstream comic “some place that was so completely off-the-map.” (Kavanagh,

2000)

In either case, not everyone is familiar with Watchmen,

and some are only as acquainted as cultural osmosis will afford. Don’t worry, I

won’t be presuming any prior knowledge. I AM, however, going to be digging in

deep for this one, folks, and we’ve got a hell of a lot of ground to cover. So

grab a cuppa, sit back, and contemplate the death of American mythology with

me.

Oh, and one more thing (one…Moore thing? No? Ah,

forget it) …

Curmudgeon Media started out as a film thing. Soon,

it became a video games thing, too. And yes, I know, I’m the blog’s

resident film guy. And no, I have zero intention of covering any of the

cinematic/televisual adaptations in detail because they’re all vastly less

interesting. Nonetheless, if y’all wouldn’t mind indulging me for a moment, I’d

like to talk the hind leg off a donkey and ramble about the greatest comic book

ever written.

Let’s rewind the Doomsday Clock and take things from the

beginning, shall we?

Setting the scene: Where did Watchmen come from?

|

| Watchmen writer, Alan Moore. Source, IMDb: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0600872/mediaviewer/rm4255139584 |

Our first stop is the mid ‘80s. Alan Moore is an unusual

writer, one who cares little for reductive concepts like “high art” or

“low art”, etc. As such, Moore “saw comics on the same continuum as novels and

movies, and would apply the same critical and creative disciplines.” (Jensen,

2005). As a writer, he breaks the mould, especially where comics are concerned.

While most writers were handing over 32-page documents, Moore consistently

dealt in 150 pages or more (Jensen, ibid), and according to Watchmen editor

Barbara Kessel, “Alan would give you the complete psychological profile of each

character, plus the meaning of every object in the environment.” (Jensen,

ibid). Moore concocts this revolutionary idea (well, revolutionary for

the time): to write a superhero story utilising disused characters, with whom he

could basically do whatever he wanted. It would be akin to being handed

the keys to an empty block of apartments, and being told to decorate in

whichever way pleases you most. Although the ultimate product of Watchmen

would deviate from this initial plan, this was the preliminary idea which

stoked the flames. Moore states: “Wouldn't it be nice if I had an entire line,

a universe, a continuity, a world full of super-heroes—preferably from some

line that has been discontinued and no longer publishing—whom I could then just

treat in a different way” (Cooke, 2000).

“I'd just started thinking about using the MLJ [comics] characters,”

says Moore, “just because they weren't being published at that time, and for

all I knew, they might've been up for grabs” (Cooke, ibid). That is to say,

Moore was initially planning on hijacking a slew of superheroes from MLJ comics

– now Archie comics – with which he could spin a story that would deviate,

in some way, from the traditional superhero narrative. Within the world which

he would weave, Moore would reveal “a reality that was very different to the

general public image of the super-hero” (Cooke, ibid).

|

| Front cover of The MLJ Companion: The Complete History of the Archie Super-Heroes (2016). Copyright - 2016 TwoMorrows Publishing |

Obviously, Moore’s proposal was a success, but with one

major caveat. Moore wanted to use pre-established, seemingly-abandoned

characters which DC had obtained from Charlton Comics. Given the direction in

which he planned to take the plot, however, he was met with resistance from

Dick Giordano – then vice president/executive editor of DC. Giordano had no

intention of handing over a bunch of characters who likely wouldn’t have

survived the story. “DC realized their expensive characters would end up either

dead or dysfunctional” (Jensen, ibid), thus “couldn't have really used them

again after what we were going to do to them without detracting from the power

of what it was that we were planning” (Cooke, ibid).

That whole thing about “detracting from the power” of the

story is important, but we’ll come back to that. In either case, on with the

story!

By Giordano’s recommendation, Moore began shaping his own,

original characters using the Charlton superheroes as a template (Cooke, ibid).

It’s pretty straightforward to map this out, actually – you can quite easily

draw a line connecting Captain Atom to Dr. Manhattan, for example. Both

characters are superheroes with a nuclear edge and “the shadow of the atom

bomb” looming ominously above them (Cooke, ibid).

|

| Dr. Manhattan (left) and Captain Atom (right). |

With the indispensable hands of artist Dave Gibbons and

colourist John Higgins, Moore brought Watchmen into fruition.

In Gibbons’ own words, the crew realised that they could create

their own archetypes “and tell a story about all superheroes. What were their

motivations? How would their very existence change the world?” (Jensen, ibid).

Conjunctionally, Moore stated that “the ’80s were worrying. ‘Mutually assured

destruction.’ ‘Voodoo economics.’ A culture of complacency… I was writing about

times I lived in.” (Jensen, ibid). It can be said, then, that there’s a realist

dimension to the story as well as a socio-historical one – two facets

which are essential to the fabric and identity of Watchmen.

What is Watchmen?

[This segment is aimed specifically at those who aren’t

familiar with Watchmen beyond the title, so if you’ve read the comics,

feel free to skip ahead to the next section. Otherwise, read on, folks!]

Watchmen begins with a murder. Eddie Blake, the

alter-ego of ex-hero The Comedian, is found slathered all over the

pavement beneath his skyrise apartment like a disgusting piece of toast. Enter

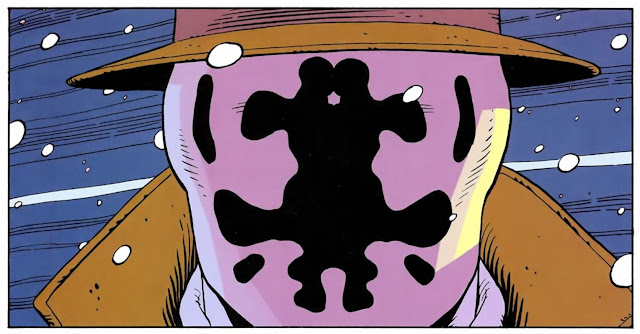

Rorschach (aka Walter Kovacs), the character whose image is most

synonymous with Watchmen. Next to the blood-stained smiley, the formless,

shifting blobs of Rorschach’s mask are something of an icon. The character’s

centrality to the story is befitting of his iconography, though – Rorschach

provides most of the narration, and is thus our way-point into the narrative.

|

| Rorschach. Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

Rorschach is a ruthless, unforgiving vigilante with a penchant for incredible violence. Think The Punisher, but with more film noir, detective-y vibes. At the time of Blake’s death, Rorschach remains the only active masked hero. After surmising that Blake is The Comedian, Rorschach theorises that someone is out for blood – superhero blood. His suspicion of a hero killer throws him into contact with old associates, fellow members of a (now defunct) team of vigilantes called Crimebusters. Among them: Jon Osterman (aka Dr. Manhattan) and his lover, Laurie Juspeczyk (aka Silk Spectre II); Dan Dreiberg (aka Nite Owl II); and Adrian Veidt (aka Ozymandias). For the sake of…I don’t know, time (?)…I’ll leave the plot at that, and visit specific plot elements as and when the occasion arises.

Let’s have a quick look at the rest of these characters!

Nite Owl II is your typical Batman-type deal. He’s got the

most elaborate costume of the bunch, he makes his own gadgets, hell, he’s

practically got his own Batcave, if not a little toned-down. Beyond

that, his abilities mostly revolve around his advanced combat skills. Similar

in this regard is Silk Spectre II, though she doesn’t come equipped with a vast

array of devices or a utility belt. I lump these two characters together for

the fact that they’re the most ordinary of the bunch. They’re basically

acrobats with superior aptitude in battle.

|

| Silk Spectre II. Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

|

| Nite Owl II. Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

Ozymandias, while also an unparalleled hand-to-hand

combatant (and a literal acrobat), is a cut above on account of his

ridiculous intellect. Dubbed the “smartest man alive” – a title which he humbly

brushes off, for the most part – Veidt’s brain could be considered somewhat

superhuman.

|

| Ozymandias. Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

The Comedian is easily the most morally reprehensible of the roster. Murderer, attempted rapist, gun-toting lunatic - he's made plenty of enemies, and he doesn't care. Even more so, he actively revels in the nihilistic brutality of life. To him, it's nothing but a big joke - hence the name. Next to Dr. Manhattan, The Comedian is among the only masked vigilantes to be willingly conscripted by the government. As such, to describe him as militaristic would be an understatement.

|

| The Comedian. Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

On a different level entirely is Dr. Manhattan, the

only true super-hero of the roster. Boasting an omniscient consciousness

and the ability to literally manipulate matter on a molecular level, he’s

more-or-less a god. He also perceives all of history at once, he can teleport,

and he’s immortal. So…yeah. More-or-less a god.

|

| Dr. Manhattan. Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

Franchising Watchmen

The intricacies of these characters will be revisited where it’s necessary, but for now, a question: what about this story makes it so that it just doesn’t fit within DC’s mythos?

Well, I suppose we could start with the surface-level stuff.

For instance, we’ve established that Moore’s propensity for writing unfathomably

detailed and lengthy scripts for his comics was – and still is – a

rather unique quality. One might go as far as to say that the depth of his

stories make them alien to the standard set by the rest of DC’s canon. This

seems a little reductive, though – after all, it’s not like Moore is the only

writer capable of delivering a good script. You might also recall that he

produced The Killing Joke in 1988 – a take on Batman which has become a

staple of The Caped Crusader’s milieu, and a definitive depiction of The

Joker. It’s doubtless that Moore’s writing style meshed pretty perfectly with

the DC universe in that case; why should Watchmen be any

different?

|

| Cover page for The Killing Joke (1988). Copyright - 2008 DC Comics. |

If I were to try and put my finger on it, I’d say that Watchmen

is an entirely different beast from anything Moore has written before or since.

Indeed, he’s got a flare for the gritty and the realistic, but we’re not

trading in terms of angsty, edgy, Zack Snyder-brand grit. That kind of grit

lacks teeth. What Moore imagines is dour, yes, and it’s violent and sad.

But it’s also extremely sincere and serious. Where Snyder overpopulates his

stories with angry men growling at each other, and an abundance of the colour

grey, Moore tops off every issue of Watchmen with an essay or a biography

excerpt. Is this the kind of writing which gels with the rest of the DC?

There’s also the idea (which I promised to revisit) that

reusing characters from Moore’s decisive vision would result in “detracting

from the power” of their plan. This is a much more sensible explanation – Moore

had a definitive idea of what he was going to do, the direction he’d take,

who’d live and who’d die, etc. It might be reasonable to suggest that

introducing these characters into the overarching world of DC would be

“disrespectful” to Moore’s artistic integrity. As far as that’s concerned, no

one’s to say but Moore himself. More importantly, however, Moore’s take on

superheroes is scrutinising down to their very fabric. The world he creates not

only primes the very concept of superheroes for criticism, but carefully

calculates a realistic depiction which just doesn’t mesh with anything

else in DC’s various, sprawling story lines – or any other comic, for that

matter. I’ll expand on this realism soon enough.

Above all, though, there’s the matter of contemporaneity. As

previously discussed, Moore was drawing upon events entirely specific to

the zeitgeist of the times. His writing was, therefore, grounded inseparably in

cold war history and anxieties. Carl F. Miller asserts that “just as crucial as

the graphic novel form to the success [of Watchmen]…was the historical

moment in which these works were written” (Miller, 2010, p.51). Frankly, that’s

all there is to it – the story he imagined is so deeply rooted in the cold war,

and depriving it of that context would be to take a wrecking ball to its

potency.

That said, you can understand my unease seeing these

characters propped up next to the likes of Superman and the rest of these

traditional hero-types. Recent instalments like Doomsday Clock (2017-2019)

exemplify this. The biggest head-scratcher, I must admit, was seeing that Wally

West (The Flash) will become Dr. Manhattan in Generation Zero

(forthcoming). Hopefully, as I delve into the next section, the wide berth

between the “heroes” of Watchmen and those of traditional comic books

will become clear.

|

| Doomsday Clock (2017-2019). Copyright - 2017 DC Comics. |

Alan Moore’s Realism and the Death of American Mythology

|

| Cover page for Watchmen (1986). Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

In contrast to the Golden Age

comics of the 1930s and ‘40s, these three Dark Age comics [Crisis on Infinite

Earths, Watchmen, and The Dark Knight Returns] spawned a standard of moral

ambiguity and the demolition of heroic mythology. (Miller, 2010, p.50)

Initially, I had planned to divide this article into nice,

clean sections. My original idea revolved around talking about Moore’s

realistic take on the superhero archetype, and then delving into the death of

American mythology, separately. But, as my extremely unsuccessful career as an

asphalt-paver has taught me, things rarely work out so smoothly. Indeed, Watchmen

is not a story so simple as to be neatly picked apart like a fresh corpse, ripe

for the autopsying. It’s more like a corpse that’s been stewing underground for

a few months, mystifying the cause of death and…uh…

I think this metaphor is getting wildly out-of-hand.

In either case, here’s my point - the realistic take which

Moore adopts in Watchmen is so closely intertwined with American

mythology that the two can’t reasonably be considered apart from one another.

The question all seven of my readers may be asking is this:

what, exactly, does ol’ Curmudgeon mean by mythology? Are we talking

about mythology the likes of ancient Greece, something Herculean? Well, the

answer is: yes and no. When I say myth I refer to a story with a

somewhat folk tradition, belonging to a particular culture. This can

mean a Herculean myth, but it could also mean something a little more

amorphous. The American Dream is an excellent example of this. In fact,

the good ol’, star-spangled, American Dream is something which we’ll return to

in subsequent portions of this article.

Superheroes are a form of myth. Umberto Eco’s 1972

text The Myth of Superman outlines this in fairly simple terms:

In an industrial society…where

man becomes a number in the realm of the organization which has usurped his

decision-making role, he has no means of production and is thus deprived of his

power to decide…In such a society the positive hero must embody to an

unthinkable degree the power demands that the average citizen nurtures but

cannot satisfy. (Eco, 1972, p.14)

So the mythical identity of a superhero is – as you could

probably guess – a method of wish-fulfilment for the disenfranchised masses.

Eco goes on to state:

…from a mythopoeic point of

view…Clark Kent personifies fairly typically the average reader who is harassed

by complexes and despised by his fellow men; through an obvious process of

self-identification, any accountant in any American city secretly feeds the

hope that one day, from the slough of his actual personality, a superman can

spring forth who is capable of redeeming years of mediocre existence. (Eco,

1972, p.14)

In the modern world, the flights of fancy of fantastical

fables – like those of Superman – are mythological in their fulfilment of a

mass, cultural desire. This is something which Moore seemingly recognises and

voices in the text itself. Let’s return to Dan Dreiberg, Nite Owl II, for a moment.

In Issue 7, A Brother to Dragons, Dreiberg and

Juspeczyk engage in an…awkward sexual encounter. After a fall-out with Dr.

Manhattan, Juspeczyk takes refuge in Dreiberg’s home, and the two grow closer

by the day. The more we hover the magnifying glass over Dreiberg, the more he

resembles Clark Kent, though he isn’t acting. He’s nervous and neurotic in many

ways. He’s timid, like a deer in headlights. Most importantly, however, he has long

since dropped the cape-and-spandex act for a fairly regular (if not plain)

lifestyle. He and Juspeczyk share a romantic moment after she notes his

“ravishing” good looks without glasses (perhaps another poetic symmetry with

Clark Kent). One thing leads to another, and pretty soon, the clothes come off.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

But, like most men his age, he suffers a little…engine

trouble, to put it delicately. He’s the real Clark Kent, he’s the

disenfranchised, white-collar man of Eco’s musings, his existence is “mediocre.”

His impotence is more than just literal – it’s an analog for the impotence

experienced by the average Joe.

This is the impotence…I mean…importance of the

superhero myth. It’s a manifestation of the desires of the impotent. It’s

fitting, then, that it takes a return to vigilantism to cure Dreiberg of

his…engine trouble.

So, we’ve explored the mythological aspect a little. How,

then, does Moore’s realistic depiction of superheroes tie into mythology, or

the death of mythology, as I so absurdly suggested? Well, folks, in for

a penny, in for a pound, as they say. Let’s dig deep and dive in.

For the sake of simplicity – or as much simplicity as I can

afford with a text as complicated as Watchmen – I’ll hand-pick two

characters which I feel perfectly embody Moore’s realistic take. After we have

a peek at their respective realism, I’ll try my utmost to explain how

they entail a death of mythology.

Dr. Manhattan

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

There is a prophetic quality to the death of Jon Osterman

and the subsequent birth of Dr. Manhattan from his ashes. The non-linear manner

in which Dr. Manhattan experiences time makes it so – the events, as he calmly

(if not indifferently) narrates to us are inevitable.

The beginning of Osterman’s trajectory is the atomic bomb.

August 7th, 1945: 16 year-old Jon Osterman practises repairing a

pocket watch with the aim of becoming a watchmaker (Issue 4, Watchmaker).

His father bursts into the room brandishing a newspaper, its front page

distinguished by the shape of a mushroom cloud.

“Forget pocket watches, have you seen the news?” his father

says. “They dropped the atomic bomb on Japan! A whole city, gone! … Ach! These

are no times for a repairer of watches …”

“This changes everything”

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

By 1958, Osterman graduates with a PhD in atomic physics.

The coming of the nuclear age is codified into the character from the start.

By ’59, Osterman falls in love with Janey Slater – a

character who’s something of a footnote, but important nonetheless in depicting

the inexorable flow of events leading to the incident that changes

everything.

|

| Jon Osterman (left) and Janey Slater (right). Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

“It’s July, 1959. I’m returning to New Jersey on vacation, visiting old university friends. Janey shares the trip from Arizona. Her mother lives in Jersey. She calls home from the station, but nobody answers. We visit the amusement park, killing time until her mother returns.”

When Janey’s watchstrap breaks, “a fat man steps on

it” before they can retrieve it. The fat man – obviously a nod to the

nuclear bomb of the same name – is the next piece of the puzzle. Osterman fixes

her watch, but leaves it in his lab coat in the I.F. chamber.

He returns for the watch, but the chamber door shuts behind

him and locks automatically. “The generators warm up for this afternoon’s

experiment…”

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

Indeed, Osterman is fried in the nuclear testing facility.

“There’s nothing left to bury.” Shortly after, Dr. Manhattan pieces himself

together out of nothing. A news anchor declares: “the superman exists, and he

is American.” Janey is scared because “everything’s changed.”

The various references tying Dr. Manhattan to the nuclear

phenomenon are numerous, deliberate, and incredibly relevant.

Even his name is a reference to the famous Manhattan Project which

yielded the first nuclear weaponry. But we’ll come back to that. For now,

another question:

What about Moore’s depiction of this “superman” makes it realistic,

per se?

Well, let’s revisit ol’ Umberto Eco for a moment:

Each of these heroes is gifted

with such powers that he could actually take over the government, defeat the

army, or alter the equilibrium of planetary politics. On the other hand, it

is clear that each of these characters is profoundly kind, moral, faithful to

human and natural laws, and therefore it is right (and it is nice) that he

use his powers only to the end of good. (Eco, 1972, p.22)

We’re dealing with beings in possession of astronomical

levels of power, yet their undoubtable code of ethics maintains their humanity.

But is this not a paradox? Eco goes on to state that an “immortal Superman

would no longer be a man, but a god, and the public's identification with his

double identity would fall by the wayside” (Eco, 1972, p.16). More important

than the public’s identification with the god would be the god’s identification

– or lack thereof – with the public. Surely, a creature of superman’s sheer

magnitude wouldn’t be human. Dr. Manhattan isn’t human, and Moore

is certain to realise this. “It’s February, 1960, and everything is frozen”,

says Osterman. “I am starting to accept that I shall never feel cold or warm

again.” (Issue 4)

Dr. Manhattan’s divine levels of power make it so that he

loses his grasp of humanity. With it, he loses his ability to care. “The

morality of my activities escapes me,” he declares as he separates a mobster’s

head from his shoulders (Issue 4). To him, we are nothing.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

Nowhere is this more prevalent than in Issue 2, Absent

Friends. As the remaining ex-members of Crimebusters watch Eddie

Blake’s casket descend into the earth, they reflect on their experiences with

him. Having both been conscripted to assist with Vietnam war-efforts, Osterman

and Blake listen to distant fireworks from the interior of a bar on V.V.N.

Night.

The two are approached by a pregnant, Vietnamese woman,

carrying Blake’s child. Blake – being the upstanding citizen that he is –

shirks his responsibility, aggressively so. “I cannot walk away from

what grows in my belly,” she says to him. “Well, that’s unfortunate, because

that’s just what I’m gonna do…forget you, forget your cruddy little country,

all of it.”

In a blind rage, she slashes Blake’s face with the greeting

end of a broken bottle. Mutilated and bleeding, Blake shoots the pregnant woman

to death, right before Osterman’s eyes. Osterman weakly protests: “Blake, don’t

do it.”

Blake does, however, make a pertinent and harrowing point.

Indeed, he shot her dead, but what did Osterman do? What did the most powerful

being on the planet do to stop him?

“You coulda changed the gun into steam or the bullets into

mercury or the bottle into snowflakes…but you didn’t lift a finger!” … “You’re

drifting outta touch, Doc. You’re turnin’ into a flake…”

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

“…God help us all…”

Anyone with even a passing familiarity with Dr. Manhattan

might be acquainted with the increasing distance between himself and the human

race as the story progresses. Unlike the archetypal superman, Dr. Manhattan is

not all-good or all-noble. The moral fabric of the superman upon which the myth

is teetering has totally collapsed. Moore doesn’t just subvert the “myth of

superman” of which Eco writes – he kills it.

Moore’s choice to synonymise Dr. Manhattan with the nuclear

phenomenon is also noteworthy, here. In this sense, it could be said that he

uses the real world reaction to the atomic bomb as a way of rendering

his fictional world’s reaction in a more realistic light. This is

written into the text in various ways, both subtle and overt. Little details,

such as the ‘fat man’ who shatters Janey’s pocket watch, or the parallel

reaction of Osterman’s father and Janey to Hiroshima and Osterman’s

transformation, respectively (both declaring that “everything has changed”).

Arguably, the most essential parallel occurs in Issue 4, after Dr. Manhattan is

conscripted by the US government to intervene in the Vietnam war.

“It’s May. I have been here two months. The Vietcong are

expected to surrender within the week. Many have given themselves up already…”

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

“Often, they ask to surrender to me personally, their terror of me balanced by an almost religious awe. I am reminded of how the Japanese were reported to have viewed the atomic bomb, after Hiroshima.”

Much akin to the world’s sublimation of the nuclear phenomenon

– in a horrifying sort of way – the coming of Dr. Manhattan is met with a very

real sense of awe and dread, in equal measure. Moore’s deliberate

employment of nuclear iconography makes Dr. Manhattan’s effect on the world

significantly more real. Consequently, it completely shatters the

popularised depiction of the superman who sees naught but adoration and praise.

The myth is beginning to rot.

There’s more to be said of Moore’s nuclear references, but

we’ll come back to that in due course. In either case…

It’s also worth noting that the concept of change –

hard, irrefutable change – is as central to Dr. Manhattan as the atomic

metaphor. However, this change and the nuclear age cannot be considered

separately. As Mary C. Brennan suggests, “The development of hostilities

between the United States and the Soviet Union seemed to make the world a more

dangerous place by creating the potential for armed conflict. In a nuclear age,

that potential threatened even to include civilians in small towns and large

cities in the American heartland” (Brennan, 2008, p.13). Simply put, the event

of nuclear armament ushered in an age of anxiety for the potential of worldwide

destruction. This destruction, as Brennan recognises, is felt in its totality

by the domestic masses. With that in mind, “1986 stands as a point in the

future [in Watchmen] … a future whose very existence is threatened by

the possibility of nuclear annihilation” (Miller, 2010, p.51). What myth, exactly,

is being killed in this instance?

This question is a little harder to answer, and is a whole

lot more…nebulous. In this case, it’s less of a myth that’s being sent

to the chopping block so much as it is the death of a way of living –

the fabric of American life itself. As Prof. Milton Glass suggests in Issue 4, “I

do not believe we have a man to end wars. I believe that we have made a man to

end worlds” – echoing the sentiment that the nuclear bomb was the “weapon to

end wars.” In this light: “We are all of us living in the shadow of Manhattan.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

As Brennan so aptly points out, the anxiety over nuclear

oblivion - which even permeated domestic life - is expertly woven into Moore’s

depiction of the superman. It wouldn’t be unusual to draw a connotative link to

the haunting words of J. Robert Oppenheimer – the ‘father’ of the atomic bomb –

“I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

As you’ve probably noticed, there’s an almost religious

stigmatism surrounding Dr. Manhattan – from the sublime terror thrust upon him

by the Vietcong, to the sheer sense of divine cataclysm evoked by his

connection to Oppenheimer’s famous quote. Glass provides a particularly

redolent statement:

God exists, and he’s

American. If that statement starts to chill you after a couple of

moments’ consideration, then don’t be alarmed. A feeling of intense and

crushing religious terror at the concept indicates only that you are still

sane. (Issue 4)

This brings us neatly onto the final – and in many ways,

most disturbing – aspect of Dr. Manhattan’s application to the death of

mythology. The thing with Jon Osterman is that he represents more

than just the death of the superman myth. He embodies the

death of the greatest myth of the Western world – the death of God.

The sheer religiosity with which people view and describe

Dr. Manhattan in Watchmen leaves a lingering sense that he has usurped

God. What’s unique about the above quote (“God exists…etc.”) is that

Osterman has quite literally taken God’s place, semantically. He has

killed God, and now he wears his skin, whether he chooses to or not. But his

omniscient, all-knowing, all-encompassing consciousness makes him privy to that

which some do not want to know. Perhaps the single most essential quote from

Osterman throughout the entire saga is this:

Who makes the world? Perhaps

the world is not made. Perhaps nothing is made. Perhaps it simply is, has been,

will always be there. A clock without a craftsman. (Issue 4)

What of this death of God? What does it matter? A quote from

J. Edgar Hoover comes to mind. “Without God as the center,” he stated, “there

would be no moral guidelines, and society would fall into chaos. Not only would

Americans lose their everyday freedoms, but their families would be destroyed

as well.” (Brennan, 2008, p.16) Of course, such a notion is reactionary and

just a little bit…you know…stupid. But, the point remains: in a

cold war world, the existence of such a being as Dr. Manhattan means the usurping

of God. And, without God, the mythological framework begins to fall apart. In

other words, “This scenario contrasted sharply with the American ideal”

(Brennan, 2008, p.16). You might also recall Nietzsche harbouring this very

belief (yes, I’m referencing Nietzsche, as pretentious and edgy as it may sound).

Warburton helpfully summarises:

If God is dead, what comes

next? That’s the question Nietzsche asked himself. His answer was

that it left us without a basis for morality. Our ideas of right and wrong

and good and evil make sense in a world where there is a God. They don’t in a

godless one. Take away God and you take away the possibility of clear guidelines

about how we should live, which things to value. (Warburton, 2011, p.172)

I’d like to say “that’s that” as far as this whole death

of God business is concerned, but really, we’re just getting started.

There’s a hell of a lot more to discuss, and it doesn’t end with Dr. Manhattan.

Next up on the agenda, it’s the face (can I call it a face?) that most people

would associate with Watchmen: Rorschach.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

Rorschach

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

The life of Walter Kovacs is something of a tragedy. Before

we get into the thick of things, it’s important to map out the key bullet

points…

His mother was a prostitute. The silhouette of her writhing

body in the embrace of a (yet another) nameless man is an image etched into his

brain since youth. That particular mental picture is perhaps one which has been

hammered into his memory by the back of his mother’s closed fist.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

His childhood isn’t exactly the epitome of the dream, urban

landscape. It seems that Kovacs was exposed to the seediness of humanity from

day one. Next thing you know, it’s 1951. Little, innocent Wally is putting out

a lit cigarette in the eye of a teenage tormentor. They grow up so fast…

Fast-forward to 1956. “When informed of his mother’s brutal

murder, he restricted his comments to one word…”

“Good.” (Issue 6, The Abyss Gazes Also)

1956 is the same year he finds “unskilled” manual work in

the garments industry. He’s 16 years old. Fast-forward again to 1962: he finds

himself entranced with a fascinating dress – “viscous fluids between two layers

latex; heat and pressure sensitive. Customer young girl, Italian name. Never

collected order. Said dress looked ugly.” (Issue 6)

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

In case you were curious, it is from this bizarre,

shifting-pattern dress that Rorschach creates his iconically unusual mask. It’s

his observations of the shapes, however, that are most interesting:

“Not ugly at all. Black and white. Moving. Changing

shape…but not mixing. No grey. Very, very beautiful.” (Issue 6).

In case you hadn’t guessed, this is symbolism. “No grey,” he

says…hint hint…Regardless, we’ll come back to that in due course.

It’s 1964, now, and the same woman who abandoned the dress

makes the front page of the New York Gazette. The chalk outline of a body

punctuates the headline: “WOMAN KILLED WHILE NEIGHBOURS LOOK ON.” (Issue 6)

“Raped. Tortured. Killed…Almost forty neighbours heard

screams. Nobody did anything…some of them even watched. I knew what people

were, then…” (Issue 6)

It is this epiphany which seems to allure Kovacs into

fighting crime. In many ways, Kovacs represents how Moore’s methodology seems

to invite realism. He imagines, deeply, exactly what kind of person, what kind

of psychology, it would take to drive someone into compulsive

vigilantism. In Rorschach’s case, the answer is quite simple: he's insane. This hearkens back to editor Barbara Kessel’s sentiments on Moore’s tendency to methodically

explore his character’s psyche and cognition (Jensen, ibid). The realism

in this case is more an example of realisation. That is to say, Moore

very thoroughly realises his characters before the ink hits the paper.

The sheer, violent extremes of his life experiences have driven him into an

almost nihilistic degree of pessimism. “I think you’ve been conditioned with a

negative world view” says his psychoanalyst – “It’s as if continual contact

with society’s grim elements has shaped him into something grimmer, something even

worse.” The realisation of these extremes through Kovacs’ development are

integral to his philosophy, but again, we’ll get to that. Regardless, the psychological

element is among the most realistic ways Moore is able to render the

behaviour of these vigilantes. Note this line in particular: “We do not do this

thing because it is permitted…we do it because we are compelled.” This

very compulsion almost seems to capture the symptom of some form

of psychological condition, like reading back the testimony of a serial

killer.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

So, what do we get when we combine this authentic

realisation of a vigilante’s psychology and exposure to only the harshest

extremes of the human condition? More importantly, in what way does this relate

to the death of superhero mythology?

Let’s start with the first question, to which I say two

words: moral absolutism.

Remember the “black and white but no grey” shtick from

earlier? That, right there, is the symbolic manifestation of Rorschach’s belief

in moral absolutism. In case that term leaves you a little cold, I’ll expound:

simply put, moral absolutism revolves around the core tenet that there is such

a thing as an objective good, an objective bad, and no in-between. The moral absolutist would suggest that actions have an intrinsic value: right or wrong. Additionally, Kovacs' ideology is "absolutist in that it does not allow for any exceptions or compromise" (Kreider, 2013, p.98). It would

appear that Kovacs’ intimate relationship with the extremes of human nature

have indoctrinated him into the belief in moral extremes, also.

What is the issue with moral absolutism? Where does Kovacs’

ideology begin to falter?

In order to answer this, it’s imperative that we take a look

at the ending of Watchmen. Over the course of Issues 11 and 12 (Look

On My Works, Ye Mighty and A Stronger Loving World, respectively),

it is revealed that Adrian Veidt, Ozymandias, is behind Eddie Blake’s murder.

On a different scale entirely, Veidt is behind a detailed and convoluted

plan to bring about the end of the cold war. The setup for Veidt’s plan and the

conclusion to Watchmen is as sprawling as it is complex, so I’ll keep

this as simple as possible.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

Veidt explains that his escapades as a vigilante faced him

with a mounting sense of failure. To fight crime is to fight a symptom rather

than a cause. Indeed, the world’s problems are much larger than any one spandex-touting

‘hero’ can comprehend. He recalls a face-off with Eddie Blake in Issue 11: “He

discussed nuclear war’s inevitability; described my future role as ‘smartest

guy on the cinder’ … and opened my eyes. Only the best comedians

accomplish that.”

“I swore to deny his kind their last black laugh at

Earth’s expense.”

So how, you might be wondering, could Veidt manage to

curb the cold war? How could he bring an end to mutually-assured

destruction? The answer is: a hoax. “Unable to unite the world by conquest…I

would trick it; frighten it towards salvation with history’s greatest practical

joke” (Issue 11). He continues: “to frighten governments into co-operation,

I would convince them that Earth faced imminent attack by beings from

another world.” Simply put, Veidt persuasively fakes an alien

invasion. As part of his plan – and as part of keeping the threat convincing

– Veidt sees to the death of an entire city of innocent people.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

Interestingly, Veidt’s plan echoes a speech from Ronald

Reagan in 1985:

I couldn't help at one point

in our discussions privately with General Secretary Gorbachev, when you stop to

think we're all God's children wherever we may live in the world, I couldn't

help but say to him: Just think how easy [your] task and mine might be in

these meetings that we held, if suddenly there was a threat to this world from

some other species from another planet, outside in the universe. We'd forget

all the little local differences that we have between our countries, and we

would find out once and for all that we really are all human beings here on

this Earth together. (Miller, 2010, p.67)

Veidt is, undoubtedly, a mass-murderer. Unfortunately, he

leaves his fellow heroes in an uncomfortable position. They could bring

him to justice, yes. However, to do so would be to reveal that the hoax alien

assault is exactly that – a hoax. The deaths of all those people would

be for nothing, and the planet would continue to cruise into nuclear

catastrophe. A vow of silence is the only course of action, the ‘heroes’ agree.

All, except Rorschach.

Such a situation confounds any morally absolute thinker. Is

it possible to do something bad for good reason? Is it "ever morally acceptable to sacrifice the interests of a few for the greater good of the many?" (Kreider, 2013, p.97). I won’t answer that question

here – frankly, I ain't smart enough - but the very existence

of such a question completely shatters Rorschach’s philosophy. “Never

compromise” … “Evil must be punished.” (Issue 12).

In the end, Rorschach is forced to confront the flaws

inherent to his ideology. When apprehended by Dr. Manhattan – who understands

the necessity to keep Veidt’s secret – he cannot concede to the truth. Even when met with a situation more nuanced that his code of ethics can grasp, he refuses to yield. Either Dr. Manhattan kills him, or he leaks the information in the name of 'justice,' and the deaths of countless innocents is for nothing. As his ideology collapses in on itself, he practically begs for death, through tears.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

Rorschach decides to remain true

to his value system, even though it could lead to the death of every person on

earth, himself included. (Kreider, 2013, p.98)

This reveal of right-wing extremist philosophy isn’t just

inherent to Rorschach. It forms a large part of Moore’s deconstruction of the myth

of superheroes as a whole. Take Ditko’s own Spider-Man, for example. No,

I’m not claiming that Spider-Man is right-wing. But consider this: the moment

Peter Parker’s justicial fist pummels the face of a petty criminal, has he not

made a lofty judgement as to an objective moral dichotomy? More importantly –

and this is where the holes in moral absolutism really begin to show –

what does it say about a character like Spider-Man if he was so ready to award

himself the power to make that distinction between the good and bad - the

deserving and undeserving of his violent “peace-keeping”?

Let’s talk about Eddie Blake, The Comedian, for a moment. If

The Comedian demonstrates anything, it’s just how easily this absolute code of

ethics can teeter over the edge into tyranny and fascism. It is here that we

can begin to understand how Moore debases the superhero mythology by chipping away

at such characters’ absolution.

An example, to make sense of this: In the 1970s, the world

experiences an aggressive uprising against masked vigilantes. This uprising is

what leads to the passing of the Keene act in 1977 – an act mandating the

government conscription (and regulation) of vigilante behaviour – and we’ll

come back to the Keene act shortly. Before we do, however, it’s interesting to

observe how The Comedian chooses to contain the situation.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

We’re in Issue 2, Absent Friends, and It’s 1977. Denizens are protesting in the streets. It gets a little rowdy – sandwich boards are flying, cans and rocks are thrown haphazardly. It’s looking like it could teeter over into a full-blown riot, if it isn’t one already. Nite Owl II attempts diplomacy – “Please,” he says, “if everybody will just clear the streets…”

Before Nite Owl can finish speaking, The Comedian takes a

more…confrontational route. “Lissen, you little punks, you better get back in

your rat holes! I got riot gas, I got rubber bullets…” It doesn’t take long

before the knives are out and the gas grenades are a-flyin’.

The striking imagery of the protesting masses, silenced by a

violent tyrant…it sure does scream “oppression,” doesn’t it? When an individual

assigns themselves not just the power to discern between an objective

good and bad, but also the authority to act upon it, it can so

quickly devolve into fascism. Rorschach’s outspoken admiration of Eddie

Blake is something of a red flag, then. In issue 6, as he sings Blake’s

praises, he simply states that The Comedian “understood man’s capacity for

horrors and never quit. Saw the world’s black underbelly and never surrendered.

Once a man has seen, he can never turn his back…no matter who orders him to

look the other way.” Accompanying these words is the image of a broken,

bloodied man, struggling on the floor of an alleyway. Rorschach walks away from

his victim in the background. What is the horrendous crime the man committed to

deserve such absolute justice? He dared to protest the self-appointed authority

of men like Blake – men like Kovacs. The Comedian, Rorschach – these are

devices with which Moore calls forth the decay of the myth of superheroes.

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

There’s a greater force at play, though. One which

constitutes not just the death of the superhero myth, but also the death of a

certain way of living, to reiterate previous comments. To understand

this, we need to ask a prevalent question: why are people rioting? Why,

exactly, would the world turn their back on the vigilantes it once heralded as heroes?

To answer that, we need to return to that motif of the

death of God once more.

There’s a particular three-panel spread from Issue 6 which I

chose to title this section, and there’s a reason for that. Within the three

panels, Rorschach expresses his own, individual musings over the death of God

and the moral wasteland He leaves behind. The setup for these panels is crucial

to understanding Rorschach’s trajectory, and crucial for comprehending his

uncompromising lack of mercy.

After having pursued a lead for the kidnapper of a 6

year-old girl, Rorschach discovers that said kidnapper has, in fact, killed

her. I won’t go into details here, but he doesn’t just kill the child – he

brutalises her. The discovery of this fact sends Kovacs over the edge. “It was

Kovacs who closed his eyes. It was Rorschach who opened them again.”

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

Indeed, it’s symbolic of Kovacs transformation into the mask

and his plunge into the abyss. Of course, he kills the kidnapper. It is his

first kill, and he burns him alive inside his apartment. And as he stares into

the plumes of smoke rising from the building, he says this:

“Looked at the sky through smoke heavy with human fat and

God was not there. The cold, suffocating dark goes on forever, and we are

alone.” (Issue 6)

It is ironic that the extremities of his experience should

push Kovacs into his unique brand of moral absolution. The irony lies in the

fact that such an absolution disappears in the very absence of God which Kovacs,

himself, notices. To reiterate J. Edgar Hoover’s panicked claims; without God,

the moral guidelines blur, and it is to the detriment of the “American ideal”

(Brennan, ibid). To recapitulate Warburton paraphrasing Nietzsche: “Our ideas

of right and wrong and good and evil make sense in a world where there is a

God. They don’t in a godless one.” (Warburton, ibid).

In this “godless” world, so to speak, how can anyone abide

vigilantes? How can anyone stomach a rigid, binary moral framework exercised by

executioners when the moral guidelines are no longer so clean cut? That

is why people are rioting. And, given Blake’s attempt to violently silence

the protesters, who can blame them? It’s all in the text – the death of God,

the death of moral assurance. But, observe this iconic interaction between Nite

Owl and The Comedian as they control the protests in Issue 2:

“The country is disintegrating” says Dreiberg. “What’s

happened to America? What’s happened to the American Dream?”

|

| Copyright - 1986 DC Comics Inc. |

Blake’s response is essential: “It came true. You’re lookin’

at it.”

There’s an overwhelming sense, here, that the myth of the ideal

American lifestyle has begun to crumble. But it isn’t that the rioting, the

debauchery, the violence killed it. This is it – Blake states quite

clearly. This violence is a result of the kind of moral authoritarianism

embodied by masked heroes. It is the child of a society which once was founded

on the moral binarism embodied by religiosity and the American ideal

aforementioned by Hoover. The issue is that the death of God – the death of

moral binarism – made it unpalatable. That is why the myth has died.

Who Watches the Watchmen (or, who cares)?

|

| Poster for Watchmen (2009). Copyright - 2009 Warner Bros. |

There’s no doubt that Watchmen is an incredible piece of

writing. After all, Time Magazine even went so far as to include it

among their list of the best novels published in the English language between

1923-2010 (see more of that here). That’s one hell of an accolade. Moore’s deft

deconstruction – or scathing criticism – of the superhero archetype etches away

at their mythology, and the mythology peripheral to their grim tales. It is for

this reason that Watchmen is so unique, and such a joy a revisit in

retrospect. It sets itself apart from the DC universe, and the complex

vigilantes concealed in its pages share so little with the rest

of the genre.

Even so, I can’t escape this feeling that Watchmen

has been more than a little misunderstood by some. This is a sentiment which

Moore, himself, recognises. In an interview, Moore stated:

I originally intended

Rorschach to be a warning about the possible outcome of vigilante thinking.

But an awful lot of comics readers felt his remorseless, frightening,

psychotic toughness was his most appealing characteristic — not quite what

I was going for. (Jensen, ibid)

Where does that leave us? The misplaced romanticism of

Rorschach’s ruthless drive isn’t just a misunderstanding of the character. It’s

a misunderstanding of Moore’s entire critique, and a huge portion of the text.

Indeed, there are some (possibly right-wing) thinkers who

sling perhaps unwarranted praise in Rorschach’s direction, and they’re entitled

to. But it doesn’t stop at that. Of course, Watchmen has seen two cinematic

adaptations: Zack Snyder’s 2009 film, and the current HBO series (2019-). Are

either of them up to the standard set by Alan Moore?

The short answer is – in my opinion – no. The Snyder film is

mostly faithful, and it finds some creative ways to adapt the more medium-specific

stuff. The Prof. Milton Glass essay, for example, the key points of which Snyder

truncates into a television interview. The movie lacks depth, though, which is

likely a symptom of its length compared to the longer form of the graphic

novel. For instance, the scene mapping the timeline leading to Jon Osterman’s

transformation leaves all the interesting, nuclear imagery – the fat man

stepping on the watch, Osterman’s father and Hiroshima – tossed to the

cutting-room floor. It maintains only the essentials to convey the basic plot

elements. Unfortunately, adopting this kind of methodology is to deprive Watchmen

of its substance, subtext, and unique charm. It’s salvaged by some strong

performances from the likes of Billy Crudup and Jackie Earle Haley – Dr.

Manhattan and Rorschach, respectively – but it also throws some characters to

the wayside. Laurie Juspeczyk, for example, who suffers serious underexposure

in Snyder’s film, and a frankly awful performance from Malin Åkerman. Snyder’s

film does, however, fall into the trap of overly-romanticising Rorschach.

Snyder just can’t help himself, it would seem. He’s got a fetish for gruff

badasses, and presents the most gruffly badass Rorschach imaginable.

|

| Poster for Watchmen (2019-). Copyright - 2019 Warner Bros. |

The HBO series makes up for this in many ways. In the

series’ timeline, Rorschach is dead, and a hauntingly KKK-esque cult is left in

his place. They martyr him, wrongfully so. Although the HBO rendition

capitalises on Kovacs absurdly right-wing agenda which Moore intended, it

simplifies it in a way which fails to capture the nuance of the original. It

trades in the intricacies of moral absolutism, American mythology and ideology,

and the various concepts central to the cold war zeitgeist. In their place, it

wears a much simpler colour of “right-wing extremism = bad.” And they’re correct,

I suppose. Right-wing extremism does equal bad…but I still feel a

little…cheated.

Then again, the HBO series side-steps most of the issues one

might find with adaptations by basically…not being an adaptation. Its

story is mostly divorced from the 12-part comic which preceded it. It sort of

goes in its own direction, although this is certain to present its own problems.

As addressed, it lacks nuance, especially when stacked against its legendary

source material. More specifically, however: they’re competing with one of the greatest writers of all time.

Damon Lindelof, on the other hand…well, let’s just put it this way: I’m fairly

sure he delivers all of his scripts scrawled on the back of a used

napkin.

But then again, there’s the question of whether or not Watchmen

should be adapted at all. As it turns out, Watchmen nearly saw

itself on the silver screen in the late ‘80s, with Terry Gilliam (Brazil

[1985], 12 Monkeys [1995]) set to direct (Jensen, ibid). Of course, the

project never came into fruition, but the original screenwriter, Sam Hamm (Batman

[1989]) had this to say:

I was coming off writing

Batman when I was asked to take a whack at it. I thought it too unwieldy to

compress into two hours. The comic really is a spectacular piece of

architecture. Trying to replicate it [was] just impossible. (Jensen, ibid)

If you’re familiar with Moore, you might have noticed that

the author takes a rigid stance against the adaptation of his work:

My book is a comic book. Not a

movie, not a novel. A comic book. It’s been made in a certain way, and designed

to be read a certain way: in an armchair, nice and cosy next to a fire, with a

steaming cup of coffee. Personally, I think that would make for a lovely

Saturday night. (Jensen, ibid)

Maybe, with that in mind, a retrospective on Watchmen

is all there should be, and we should leave it at that. It’s been and it’s gone

– the cold war is over. But who’s to say…?

A message from the writer...

Hello there, folks! If you made it this far, I've got something to say to you...

Thank you. Seriously, thank you.

I've been mulling over writing this for a hell of a long time, and it's been challenging. I haven't attempted anything of this magnitude before.

I also understand that lengthy pieces of analytical writing aren't exactly all the rage these days. But that's why I feel the need to sincerely thank those who're reading this little epilogue.

I worked really hard to produce this article, and it's become truly special to me. I hope that you got something out of reading it, too.

In either case, I'll be seeing y'all in the next one. It'll be a nice, short, digestible one - you can be sure of that. Bibliography is down below, just in case you're interested.

Take care, folks. Yours,

The Curmudgeon

- Brennan, Mary C. “The Cold War World,” in Wives, Mothers, and the Red Menace: Conservative Women and the Crusade against Communism. Colorado: University Press of Colorado, 2008:13-30.

- Cooke, Jon B. “Toasting Absent Heroes: Alan Moore discusses the Charlton-Watchmen Connection.” Two Morrows, Jun. 16th, 2000. Accessible from: https://www.twomorrows.com/comicbookartist/articles/09moore.html

- Eco, Umberto. “The Myth of Superman.” Trans. Natalie Chilton. Diacritics vol.2, no.1 (1972):14-22.

- Jensen, Jeff. “Watchmen: An Oral History.” Entertainment Weekly, Oct. 21st, 2005. Accessible from: https://ew.com/books/2005/10/21/watchmen-oral-history/

- Johns, Geoff. Doomsday Clock. Burbank CA: DC Comics, 2017-2019.

- Kavanagh, Barry. “Marvelman, Swamp Thing and Watchmen.” Blather.net, Oct. 17th, 2000. Accessible from: http://www.blather.net/projects/alan-moore-interview/marvelman-swamp-thing-watchmen/

- Kreider,S. Evan. “Who Watches the Watchmen? Kant, Mill, and Political Morality in the Shadow of Manhattan” in Homer Simpson Ponders Politics: Popular Culture as Political Theory ed. Joseph J. Foy & Timothy M. Dale. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013:97-111.

- Miller, Carl F. “Worlds Lived, Worlds Died: The Graphic Novel, the Cold War, and 1986.” CEA Critic vol.2, no.3 (2010):50-70.

- Moore, Alan. Watchmen. New York: DC Comics Inc, 1986.

- Warburton, Nigel. “The Death of God,” in A Little History of Philosophy. London: Yale University Press, 2011:171-175.

Comments

Post a Comment