|

| Written by The Curmudgeon |

Ugh…

I don’t like writing lists. Well, I’ve got nothing against lists

as a concept. Shopping lists are bloody helpful. As are my daily lists

of reasons to actually wake up in the morning.

What I mean is this: I don’t like list-y journalism. Listicles.

They feel lazy to me. They’re clickbait-y. Top 10 this and Top

10 that. It’s a crash-course in how to write articles with all the flare

and inspiration of that ungraded presentation you did back in high school. You

know what I’m talking about – the one you left until last minute and basically

made up on the spot.

Regardless, we’ve made it through another decade. We’ve endured

another ten years on this nightmarish hell-world we call Earth. It’s

dog-eat-dog, every man for himself. It’s full Mad Max out there, baby –

even if it doesn’t look it, it sure as hell feels like it. Or maybe I’m being dramatic

to justify abandoning my creative integrity to make a listicle.

My self-respect aside, I thought it’d be a bit of fun to

review the last decade, and pick out a few movies from the last ten years which

I’d be comfortable calling favourites.

Before I begin, the following is my personal opinion.

These are my picks for the best films of the decade. Not to mention the

fact that there are a lot of amazing movies from the past ten years, and I

don’t want to be writing a list forever. All clear? Good.

Without further ado…

The Secret World of Arrietty (2010)

The Secret World of Arrietty is an adaptation of Mary

Norton’s 1952 children’s fantasy novel, The Borrowers. The gist is this:

there exists a race of incredibly small people – no larger than your index finger

– who scurry about the nooks and crannies of your abode, in secret. To survive,

they simply borrow that which you won’t miss, or perhaps, won’t even

notice has gone. On account of their miniature stature, they don’t require much

– a single sugar cube could keep them for months, for example.

Protagonist Arrietty (Saoirse Ronan) is a borrower.

Young and adventurous, she yearns for her first outing to steal that which

won’t be missed. However, a chance encounter with sickly Shô – a

young, human child, stricken with an ambiguous illness – causes herself and her

family to be discovered.

The movie is amongst the repertoire of the acclaimed Ghibli

animation studio, and an early outing for Hiromasa Yonebayashi in their ranks – a name which will

be revisited in this list. In the typical Ghibli spirit, the film is

gorgeous. There’s a subtle satisfaction to how carefully considered the physics

are in this imaginary world. Take the way this tea pours out of their tiny pot,

for example:

The aesthetics are only part of what makes a movie, however. At

the core of Yonebayashi’s story is a girl who is existentially overwhelmed.

Faced with Shô – a creature of such great magnitude – Arrietty cannot help but

abandon her vigour and adventurousness for existential contemplation. She’s

struck with the sudden whiplash of realising how small she truly is;

literally, and figuratively. Shô, however, is small in his own way. Since his

illness demands that he is house-bound, his world is small and stifling. In

this sense, the two characters are forced into dialogue with their own

mortality – Arrietty, on account of her diminutive stature and physical

insignificance, and Shô, because of the looming threat of untimely death.

It is this aspect of The Secret World of Arrietty which

really resonated with me, personally. Watching the two characters overcome

their depression by inspiring one-another is something to behold.

Hugo (2011)

What if I told you my favourite Martin Scorsese flick isn’t Goodfellas

(1990)? It isn’t The Departed (2006), it isn’t Mean Streets

(1973), it isn’t Taxi Driver (1976), although the latter comes pretty

close.

No, my favourite Scorsese film is the one no one talks about, or

cares about, for that matter.

In a bizarre change of pace for the legendary director, Hugo

is a children’s movie inspired by the French film maker, Georges Méliès. The

plot is a fairly standard mystery. An orphan, the titular Hugo (Asa

Butterfield), finds himself enthralled by a plot involving his deceased father

and a clockwork automaton. But the plot isn’t really what interests me about Hugo.

What makes this movie so memorable is Scorsese’s affectionate ode to a

film maker he loves and respects deeply. If you’re unfamiliar with Méliès’ work

– as I mostly was, prior to seeing the film in 2011 – the director traded

mostly in magical, whimsical tales, such as A Trip to the Moon (1902).

His movies were spectacle in its purest form, presenting bizarre imagery and

grand illusions. In this sense, Hugo takes on an almost biographical

aspect; not that it is true to Méliès life, but that Scorsese writes the film

much in the same way Méliès might write a film about himself. It’s whimsical

beyond comparison, it’s sentimental, and Scorsese’s passion for a director who

inspired him is seeping from every pore.

It’s honestly a shame this film went as underappreciated as it

did.

Wolf Children (2012)

I’ve got a confession to make, folks.

I don’t like Mamoru Hosoda.

I don’t like him one bit.

Well, that’s not to say I don’t like him, as a person. I’m

sure he’s swell. I just don’t like his movies all that much. I honestly believe

they’re some of the most overrated movies in the medium.

My biggest issue with his films is that they demand too much of

the audience, usually by derailing the plot in a way which doesn’t make sense,

or is frankly unsatisfying. This is a process I refer to as ‘Mamoru

Hosoda-ing.’ A stupid term? Yes. But you know how you get to the end of The

Boy and the Beast (2015), and it turns out that one kid who had about 5

minutes of screen time is the big-bad? Or how, in The Girl Who Leapt Through

Time (2006), it is revealed that the titular girl’s friend who

barely spoke is a time-traveller? That’s what I call Mamoru Hosoda-ing.

In either case, there’s one exception to this rule. Wolf

Children is the only Hosoda film which I believe meets its reputation.

An emotionally relentless film, Wolf Children revolves

around a woman, Hana (Aoi Miyazaki) who falls in love with a lycanthrope. As

the title would suggest, she bears his wolf children as well. Surprise

surprise.

When the unthinkable happens and Hana is left to raise the

children alone, their half-human-half-wolf aspect begins to take on a more

figurative purpose. That is to say, Hosoda utilises the unique inter-species

tendencies of these two children as a way of exploring the trials and

tribulations of motherhood. Tracing the children’s development from babies well

into adolescence, Wolf Children is a touching and detailed portrait of a

struggling, single parent desperately trying to adapt to the evolving problems

which accompany her offspring as they inevitably grow older, and drift apart.

Don’t watch this one if you don’t like weeping convulsively,

because that’s exactly what you’ll do.

Her (2013)

Given director Spike Jonze’s partnership with screenwriter Charlie

Kaufman, Her presents a unique situation, given Jonze’s credit as both

director and writer. Clearly, Jonze learned much from his screenwriting

associate, because Her is an almost perfect movie.

Set in a not-so-distant future (characterised by an overabundance

of technology not unlike that which we use today), Her captures the

romance between lonely, amorous Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) and A.I. Samantha

(Scarlett Johansson). A bizarre premise, yes; functionally, a man falls in love

with his phone. But at its core, Her is a contemplation upon the rapid

advancements in technology, and the distance between human beings which might

result.

Nowhere is this more prominent than in the opening scene of the

film. Theodore pours his heart out in a touching, deeply personal monologue.

The speech depicts some remarkable, idiosyncratic love between himself and an

unseen other. After a while, however, we realise he’s not speaking for himself,

but is writing a letter on someone’s behalf - for a woman he’s never met.

That is Theodore’s vocation in the world of Her – he writes

personal letters for other people. If the haunting bastardisation of human

communication isn’t totally obvious in this case, I’m not sure what else to

say.

The film is bolstered by some all-round incredible performances.

Joaquin Phoenix is a popular performer at this point, but I’d like to underline

how incredible Scarlett Johansson is in this movie. She has a real, tangible

on-screen presence without ever actually being on-screen.

When Marnie Was There (2014)

I don’t want to overpopulate this list with Studio Ghibli films,

so I’ve had to do a toss-up between The Wind Rises (2013) and When

Marnie Was There (2014).

Ultimately, I chose the latter, simply because it resonates with

me on a much more personal level.

From the aforementioned Hiromasa Yonebayashi, When Marnie

Was There demonstrates exactly how the burgeoning Ghibli director has

differentiated himself from Hayao Miyazaki. Contrary to Miyazaki’s typically

whimsical filmography, the movie is, in a term, emotionally raw.

The plot centres upon a twelve-year-old, asthmatic misanthrope by

the name of Anna. Sent to stay with relatives in the countryside, Anna develops

a kinship with a mysterious girl – Marnie – who may or may not even exist. I

don’t want to say any more about the story, because there’s much to be enjoyed

going into the film knowing as little as possible as far as that’s concerned.

Anna is among the most unique and complex Ghibli protagonists.

She’s not strictly easy to get on with; her deep self-hatred and fear of

abandonment manifests in bouts of outward aggression. She has a tendency to

say and do unkind things which she doesn’t mean, but she’s all too self-aware,

resulting in a violent cycle of inward resentment. Indeed – Anna is severely

depressed, at just twelve years of age.

Yonebayashi uses the friendship between Anna and Marnie to explore

the insecurities of both characters, making for a satisfying, three-dimensional

dynamic. As we begin to peel away the coarse rind which hides the deep,

cognitive issues plaguing our protagonist, the plot gradually reveals those

moments in her history which have left her so troubled.

This is a film to be enjoyed by anyone with any experience in

turbulent mental health, especially as a child. Sometimes, I’ll listen to the

film’s outro song, Fine on the Outside by Priscilla Ahn. Taken from the

perspective of Anna, the line “would you cry if I died” is a tragic thing to

spawn from the mind of a such a young girl.

Over the Garden Wall (2014)

Is Over the Garden Wall a movie? Not strictly. But I’m

including it because it’s only ten episodes long, eleven minutes a pop. All in

all, it’s basically a movie-length miniseries, or a movie divided into several

parts.

It’s difficult to capture, in words, why Patrick McHale’s animated

opus is so incredible. I’ve contemplated writing about it many times, but it

remains elusive.

Two children, Wirt (Elijah Wood) and Greg (Collin Dean) are lost

in the woods. There’s no indication of where they came from or how they came to

be here – at first. Accompanied by a talking bluebird named Beatrice (Melanie

Lynskey), the two attempt to navigate the winding woods and peculiar pastures

of The Unknown.

It truly is lightning in a bottle. It’s got a very distinctive,

anachronistic tone, blending American Gothic traditions with a more

contemporary storytelling sensibility. This is mostly due to the

fish-out-of-water protagonists, who clearly act and behave like children of the

modern day, in contrast to the old-timey-Disney setting they occupy. This dynamic

certainly lends itself to some of the more humorous aspects of the show, as we

watch the perfectly regular Wirt attempt to apply his modern logic to

situations which don't call for it. When he sees Beatrice speak for the first

time: “a bird’s brain isn’t big enough for cognisant speech” – a comment which

Beatrice, understandably, is offended by.

Frankly, it is the characters which are the easiest selling-point

to communicate. To call Wirt the straight-man would be a disservice to his

character. He’s intelligent, but dorky, and his tendency to melodramatically

burst into free-form poetry is cute, if not slightly pathetic. He is also a bit

of a coward, a trait which he gradually irons out over the course of the plot.

He is contrasted perfectly to his insane, younger half-brother, Greg, who

speaks almost entirely in nonsense. It isn’t so much that Greg is brave.

Rather, he’s too naïve to recognise danger, and will often just go wherever his

whim takes him. Beatrice, finally, is the misanthropic curmudgeon of the trio.

Morally ambiguous, she is the most at-odds with the group, and her

motives are suspicious from the start. To me, her gradually developing

admiration for, and friendship with, Wirt forms the heart of the show.

Ultimately, Over the Garden Wall presents a unique

aesthetic situation. It’s funny, loaded with unique, Gothic charm, it’s got a

wonderful cast of characters, and the journey therein will make you want to

stay in the unknown with them forever.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Wes Anderson has made a name for himself by being uncontrollably

quirky. Some people hate this about him. I’ve heard many complain about ‘all

his movies being the same,’ or that his quirkiness somehow makes the films

one-dimensional.

I disagree completely, and I would even go as far as to say The

Grand Budapest Hotel is among my favourite films of all time.

Tracing the memoirs of a now-deceased writer who met with the

patriarch of a dilapidated, once-beautiful hotel, the film makes its mission

clear from the offset. As it jumps back in time from one character to the next,

finally arriving at the proverbial doorstep of one M. Gustav (Ralph Fiennes), the film conveys

in clear imagery the majesty of a hotel that once was. This is, simply, a

love-letter to a time gone by.

M. Gustav is the concierge of the hotel, and Zero Mustafa (Tony Revolori/F. Murray Abraham)– the

future owner of the establishment – is his lobby boy. As the former is

wrongfully accused of a murder he didn’t commit, the two embark on a ridiculous

adventure to solve the mystery and clear his name.

Anderson proudly constructs a Hitchcockian caper, blended with his

own personal command over visual comedy. It is this very visual comedy which is

often referred to as “quirkiness.” To say so is to discredit how effective it

truly is.

Take the scene when Gustav is arrested, for example. “She’s been

murdered,” he asserts, calmly. “And you think I did it.”

Suddenly, he runs off, as the police follow in hot pursuit.

Meanwhile, the camera doesn’t move one bit. The juxtaposition between

the sudden burst of action and the totally static perspective is funny without

the use of any actual jokes.

Anderson’s reverent toast to an older style of film making is

bittersweet, however. For every flat, old-fashioned piece of cinematography,

for every saccharine, archaic colour palette, there is the brutal reminder that

what was is no more.

For those who have seen the movie, I simply say this: “There are

still faint glimmers of civilization left in this barbaric slaughterhouse that

was once known as humanity. He was one of them. What more is there to say?”

Nocturnal Animals (2016)

Tom Ford is a genius. The man genuinely baffles me. He’s some

hot-shot fashion designer, then in 2009 he comes along and decides he’s going

to make a movie. More importantly, the movie is actually good. Really

good.

If you’ve not seen A Single Man (2009), you owe it to

yourself to see it. But I’m not here to talk about that. I’m here to talk about

his second directorial outing, Nocturnal Animals, an adaptation of Tony

and Susan (1993) - a novel by Austin Wright.

Technically speaking, Nocturnal Animals juggles three narrative

threads running in parallel. Primarily, the plot hinges upon Susan (Amy Adams),

a bourgeois living a luxurious yet empty existence. Her husband is handsome but

unavailable, and unfaithful. After receiving a manuscript for a novel written

by her ex-husband Edward (Jake Gyllenhaal), Susan finds herself reflecting

upon the past; her relationship with Edward, and how it weighs upon her

present. The story of the novel presents the second narrative thread. It

depicts a harrowing tale of a family of three – Tony, also played by

Gyllenhaal, his wife, Laura (Isla Fisher), and their daughter, India (Ellie

Bamber) – as they are unexpectedly terrorised by a group of thugs while

travelling. Ultimately, Tony’s wife and daughter are abducted, raped, and

murdered, and Tony is left stranded. Susan’s reflections upon her past serve as

the third narrative thread, as we watch her relationship with Edward crumble

and her regrets relive themselves in her mind. These three stories are

masterfully interwoven in a way that they all bear upon one another.

Edward’s novel, although extremely compelling in its own right,

makes for a fascinating portrait of the ex-husband’s overwhelming feeling of

emasculation after their egregious divorce. That Edward and the character he

writes are portrayed by the same actor is telling. That Tony’s wife and

daughter bear obvious resemblance to Susan is likewise no mistake, either. Is

it that Susan interprets the characters this way? Or is it how the characters

are described?

The visual worlds Tom Ford imagines are communicative in

themselves. The mannered cinematography of Susan’s present is controlled and

collected, yet grey and monotonous. It contrasts with the romantically warm

palette of her memories of Edward. Meanwhile, the novel presents a milieu that

is dusty and unpleasant.

Adams is perfect as Susan. The subtle differences between her

younger, happier self and her older, jaded self are measured flawlessly.

Gyllenhaal delivers two incredible performances – perhaps the most raw and real

of his career. Michael Shannon deserves a special mention, too, as the ruthless

but altruistic Sheriff, sniffing out the thugs responsible for the death of

Tony’s family. Bind this all together with a majestic score by Abel

Korzeniowski, and you’re staring down the barrel at one of the greatest films

of the twenty-first century.

The Nice Guys (2016)

You know, I never used to like Ryan Gosling. Now he’s one of my

favourite actors. The next three movies on this list are the reason why.

As you’ll know, if you’ve read my Red Riding Trilogy

article (click here for more on that), I’m a big fan of the noir genre (is it

even a genre?). Shane Black’s The Nice Guys, while a refreshing and

hilarious addition to the noir canon, went largely unnoticed.

A pulpy throwback to 1970s cop thrillers, the film sees alcoholic,

barely-functional P.I. Holland March (Ryan Gosling) attempt to track down the

missing Amelia Kuttner (Margaret Qualley). Meanwhile, aged and jaded

hired muscle Jackson Healy (Russell Crowe) is contracted by Amelia herself

to get March off her tail. When the two collide, they realise there’s more to

Amelia’s disappearance than meets the eye. What unfolds is a classic story of

corruption, scandal, and porn stars.

The film lovingly homages the ‘70s buddy-cop detective flick with

finesse, but I’d be lying if I said the whole reason this film is on the list ISN’T

because of the performances.

Ryan Gosling is an objectively funny man. He is objectively

funny. If you don’t think he’s funny, at least in this movie, you need to

get your fuckin’ head checked. His haphazard, incompetent disposition riffs

perfectly off Russell Crowe’s relaxed street-smarts.

Shane Black is known for his witty dialogue, and The Nice Guys

is his finest. A personal favourite line – from this or any movie –

occurs while March deflects a rowdy crowd of teenage girls at a birthday party:

“Jesus Christ, one at a time!” … “you just took the lord’s name in vain” says

one of them. “No I didn’t, Janet…”

“I found it very useful, actually”.

You get the point. Go watch The Nice Guys. It’s a blast.

La La Land (2016)

I imagine this will be the most unpopular pick on this list.

I distinctly recall Damien Chazelle’s throwback to old Hollywood

musicals being the most popular film on the planet for about a week before

everyone collectively decided it was too schmaltzy for them.

I was not one of those people.

I feel the need to defend La La Land on account of the fact

that it’s often misunderstood. A lot of people accuse the movie of sucking up

to Hollywood in an attempt to curry favour with the academy.

Personally, I think this is a totally surface-level criticism of

one of my favourite movies of all time (there, I said it!).

Indeed, La La Land is an homage to classic, Hollywood

musicals, but not without criticism of the Hollywood mentality. The title

itself is referential to the dreamlike unreality of the Hollywood

populace. I’ve said Hollywood so many times, it’s beginning to lose its

meaning…

I actually wrote about how La La Land criticises Hollywood

culture in one of the first pieces I wrote on this (currently readerless) blog

that I maintain for no discernible reason. If you’re interested, you’ll find

that here.

Regardless of whether the above criticism of the movie has

any salt, it’s still a passionately-made, intricate piece of cinema. The

opening number is an instant demonstration of the incredible score and

choreography, and Emma Stone’s chemistry with Ryan Gosling makes it so clear

that the duo are close off-screen as well. The fact that the two

performers sing for themselves gives a real authenticity to the numbers, and

the sheer amount of work Gosling put into learning the piano is staggering.

Plus, I’m a sucker for that bittersweet ending…

Blade Runner: 2049 (2017)

The final Gosling flick on the list, Blade Runner: 2049 is

another film I’ve written about before (see more on that here).

The fact that 2049 is actually a good movie still feels

unreal to me. Think about the current cinematic climate we’re in – remakes and

sequels to franchises from 30 years ago are spewing left, right, and centre.

Most of them are unnecessary and terrible, but bankable.

When it was revealed that a sequel to the cult classic, Blade

Runner (1982), was in production, my heart sank. I love that movie, and

there’s no way they could do it justice. However, after I saw Denis Villeneuve

was attached to the project, alongside Roger Deakins, the possibility of the

sequel being decent became very real.

2049 picks up more-or-less where the original left

off. There are humans, and there are replicants - biological androids. The

humans rule and the replicants are bound to slave labour. Keeping the “peace”

are the Blade Runners, hitmen who hunt and “retire” unruly replicants.

Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), the protagonist of the ’82 film has

gone into hiding. His replicant lover, Rachael (Sean Young), is dead. In their

wake, they left the first, birthed replicant child.

Enter Officer K (Ryan Gosling). K is a replicant Blade Runner,

entrusted with hunting his own kind. Upon his discovery of a birthed

replicant, K is delegated to the hunt once more. After all, if a replicant

is capable of child birth, what separates them from us?

Things get a little cloudy when K arrives at the very real

possibility that the child may, in fact, be him.

To say that 2049 is a good sequel is an understatement. 2049

is just an excellent movie, and it understands the philosophy of Blade

Runner quite clearly. Joe’s character arc epitomises the dilemma of the

original. What constitutes ‘human?’ Who makes that decision? Does it matter?

Roger Deakins is one of the greatest cinematographers of all time.

His incredible eye, in tandem with Villeneuve’s direction, makes for a

beautifully-realised world, and a faithful development upon the iconic setting

of the original. The film improves upon the original in many ways, providing a

much more engaging plot and genuine sense of mystery – something which

the original, admittedly, lacked.

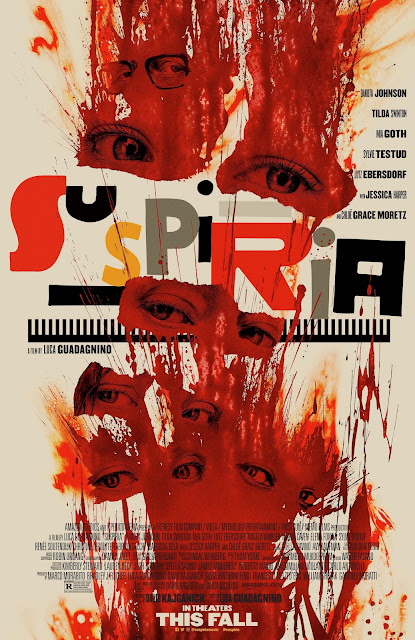

Suspiria (2018)

The 2018 remake of Suspiria does what all great remakes

should do: it divorces itself, almost completely, from the source material.

Dario Argento’s exploitation horror of ’77 is a very much a visual

creature. Director Luca Guadagnino opts for a more narrative focus, and does so

brilliantly.

The film retains its ’77 time period, and its Berlin setting. The

story can be divided into two parts: on one hand, we have the young, ambitious Susie

(Dakota Johnson), a dancer enlisted into a prestigious dance school. On the

other, we have the old and placid psychotherapist, Dr. Klemperer (Tilda

Swinton), desperately trying to understand the disappearance of one of his

patients, a fellow student of the very same school. What results is a

masterfully unfurled mystery, combining aspects of Gothic horror,

exploitation horror, and Cold War noir.

The marriage of Gothicism and Cold War noir is of particular note.

The two genres compliment each other perfectly, sharing interest in

expressionistic visuals, the sublime, and the looming sense of impending dread.

Perhaps I’ll talk more on the overlaps between Gothicism and film noir in the

future…

The performances are stellar, as well. It’s great to see Dakota

Johnson shaking off her association with the abysmal Fifty Shades of Grey

(2015). It’s Tilda Swinton, however, who really deserves the spotlight. She

plays three characters in the film, but it’s Klemperer who is the most

impressive demonstration of her talent. To watch Swinton so perfectly embody an

elderly, German, and very MALE psychiatrist is…uncanny.

Klemperer is arguably the more interesting of the two

protagonists. As far as the noir aspect of the film is concerned, he

makes for a refreshing replacement of the amoral spy or private eye. His

persistent hounding into the school’s dangerous coven of witches is not a mark

of fearlessness. Rather, it seems his advanced age and wisdom make him

indifferent to his physical well-being. All the while, the unsolved

disappearance of his wife after WWII weighs on his shoulders from start until

finish, adding an emotional edge to the story which was absent from the

original. The lump in my throat which I couldn’t seem to shake as Klemperer

discovers the fate of his beloved spouse represents everything I love about

this movie.

What are your favourite films of the decade?

There we have it – the list of my favourite movies of the decade

which no one asked for, and almost no one will read.

As for the incredibly small handful of people who do read my blog:

what about you? What are your picks for the best movies of the decade? How does

it compare to other decades in the history of cinema?

This has definitely been the longest piece I’ve

written, but I suppose that’s to be expected of a list like this. Alas, my

fingers hurt, and I’ve said too many nice things in a short period of time.

I’ll see you all next time…

Really enjoyed reading this.. succinctly observed and dissected

ReplyDeleteTa very much! What would you say are your favourites of the last decade?

Delete